“Everything popular is wrong.” —Oscar Wilde

“Any user can change any entry, and if enough other users agree with them, it becomes true.” —Stephen Colbert on Wikipedia

“If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.” —Anonymous

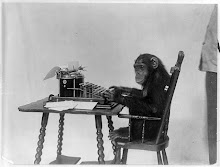

Monkey See, Monkey Do

I thought of all three of these remarks this morning when I came across a story on School Library Journal’s site detailing the decision of Encyclopædia Britannica to go the route of Wikipedia and allow for input from the public to “create, document, and share knowledge on its site.” School Library Journal continued:

Under the new plan, the carefully edited Encyclopædia Britannica will continue to exist. But there will be another section for its new “community of scholars,” where thousands of invited experts can publish their works, scholarly papers, and drafts on a wide range of subjects, from sports and pop culture to art and zoology, says spokesman Tom Panelas, adding that this may be the first time a traditional encyclopedia has taken an open-source approach.This is amusing because Britannica is the same encyclopedia that was involved in a battle with Nature in early-2006 after Nature released the results of a “study” (I use quotation marks because it’s still not clear if it was a real study or just a “piece of journalism”; I’ll get to that later) which compared the accuracy of Encyclopædia Britannica entries and similar Wikipedia entries. The study’s results were that Wikipedia is almost as accurate as Britannica.

Unfortunately, it turned out that the “study” had too many flaws in it to be legitimate (unless you’re a Wikipedia fan, of course—in which case any methodology is probably kosher as long as you get the desired result).

Quantity—Not Quality

In case you didn’t read about it, in 2005, Nature published a story describing a study that was done to compare the accuracy of Wikipedia and the Encyclopedia Britannica. The results of the study showed that Wikipedia was almost as accurate as Britannica.

There was just a little problem with the study: the procedures used in it were questionable enough to put doubt in the minds of folks who have an understanding of educational research as well as former Nature journalists.

Reviewers were given similar entries from both Britannica and Wikipedia to compare. Their job was to review the accuracy of each and take into consideration any possible omission of information.

In 2006, Natasha Loder, a former Nature writer and current Economist contributor, wrote a lengthy piece on the methodology that’s worth reading if you’re interested in the debate. The important points that she makes are:

- While the entry reviews were done by experts, the methodology was designed by journalists.

- Nature admittedly edited out parts of entries when reviewers said that the entries were poorly written. Were any of these edits counted as inaccuracies? Was there a point where inaccuracies were deemed “poorly written” and just left out of the tally? Was a “poorly written” article in Wikipedia set equal to an “inaccuracy” if something similar appeared in Britannica?

- In one instance, for the same topic, the reviewers were given an 825-word entry from Britannica and a 1,500-word entry from Wikipedia to compare. Not surprisingly, Britannica was cited for having “omissions.” When Loder checked to compare the entries, both had 1,500 words.

- Nature also admitted to having performed a cut-and-paste job on the Britannica entries, leaving the Wikipedia entries as-is. The moment that this was done, the study was no longer a blind study (as Nature suggested). This cut-and-paste job introduced a systematic bias into the study.

- Reviewers counted “omissions” in each entry and Nature’s cut-and-paste job of Britannica entries raised a final question: Which omissions were Britannica’s fault and which were perpetrated by way of the cutting-and-pasting?

Comparing Apples and Rotten Apples

One thing that wasn’t taken into consideration with the study—or “comparison” or “investigation” or whatever Giles wanted it called—was Wikipedia’s track record. If Britannica had the level of errors that Wikipedia has had, they would have gone out of business years ago.

False information about the JFK assassination; libelous entries written about Norwegian Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg and professional golfer Fuzzy Zoeller; former MTV employee Adam Curry editing his own entry to pad his résumé; an entry on Harriet Tubman with racial epithets; Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales personally altering an entry on Alan Dershowitz in an effort to censor some of the information (Wales refers to his censoring as “protecting”); the false report on the death of comedian Sinbad. These are just a few of the reported falsehoods from the last few years.

Does anyone seriously view this stuff as something that would be found in a legitimate source of information? They do.

Popularity Contest

While I was compiling the Websites that I’ve used as references for this post, I continually came across the same theme from the Wikipedia defenders: it’s a bold experiment to bring the community together in the name of information.

It doesn’t seem to matter if the information is accurate; it’s just important that everyone comes together, shares information, and makes the Website itself really popular. The concept behind the product thus trumps the final product.

What legitimizes this situation? The popularity.

For some reason pop culture plays a huge role in our culture. Someone’s popularity makes them important, even if they don’t actually accomplish something. Paris Hilton is a wonderful example of this: She didn’t actually accomplish anything to reach the level of notoriety that she did. She essentially partied her way into the hearts and minds of Americans.

Likewise, for a great deal of people the use of Wikipedia as a source of information is more a status symbol than one of intellect. If your classmate uses it as a go-to resource, you can, too. If it comes up first on a Google search (which it almost always does), it must be good.

The public at large can make it; the public at large should use it. Its popularity says that it’s good.

My guess is that Britannica is paying attention to such a situation and jumping on board. Why try to swim upriver when the majority is tubing downstream? In this case, Britannica needs an element of popularity in the picture in order to survive financially.

Granted, the bulk of their orders are probably coming from folks who order for libraries or educational institutions, but these people aren’t anymore immune from being fascinated with popularity than the next person.

Without going into detail, my job involves analyzing Websites for value and usefulness. Two years ago I had a colleague who loved Wikipedia for the very reason that I mentioned earlier: popularity. It’s very popular, she reasoned, so why shouldn’t we promote its use for educational settings?

Given this, I guess that we should have tried to promote Paris Hilton for whatever it is/was that led to her popularity.

A second theme that I found while doing this research in defense of Wikipedia is that their entry authors must cite the resources from which they found their information. On a comment thread pertaining to Stephen Colbert’s aforementioned quote, the following remark was left:

Wikipedia’s article [sic] are created by a group of individuals dedicated to spreading the truth and more people watching it to make sure it stays accurate. To edit an article you need to cite a reference to a scholarly source OR a number of trusted sources (such as 2 or 3 popular new sources) and also mention your edit in the talks page of the respective article. If you do not do the above, your edit will be taken as vandalism and reverted and a message will be left for your IP by Wikipedia to tell you that you need to do the above in order to make changes to an article.So, the question then becomes this: If you’re gung-ho about Wikipedia’s use because it’s from the “community” instead of a traditional encyclopedia publisher, aren’t you defeating the purpose of Wikipedia by requiring that one of those traditional sources (the “scholarly” or “trusted” sources) be used? Moreover, doesn’t that call into question the real need for Wikipedia? I mean, if you didn’t have those traditional sources, you wouldn’t be able to have the Wikipedia entry in the first place.

Given the state of everything else in this world, I’ll probably be accused of being an anti-community, capitalistic neo-con.

Perhaps I’ll go now and add this to the Wikipedia entry on “Wikipedia.”

References

“Britannica Gets ‘Wikified.’” School Library Journal. July 2008: 12.Cooper, Chase Edwards. “Wikiprophet.” The Tempest. 20 Apr. 2007.

Giles, Jim. “Special Report: Internet Encyclopaedias Go Head to Head.” Nature. 15 Dec. 2005.

Giles, Jim. “Wikimania 2006 Jim Giles (August 4, 2006).” Internet Archive. 2006.

Loder, Natasha. “Battle of Britannica.” Overmatter. 29 Mar. 2006.

Spring, Corey. “Stephen Colbert Causes Chaos on Wikipedia, Gets Blocked from Site.” Newsvine. 1 Aug. 2006.

Ω

No comments:

Post a Comment